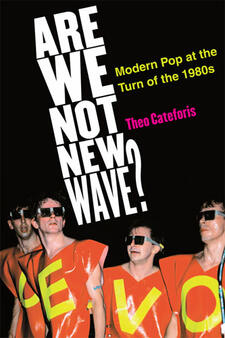

Q&A with Theo Cateforis, author of Are We Not New Wave?

New wave emerged at the turn of the 1980s as a pop music movement cast in the image of punk rock's sneering demeanor, yet rendered more accessible and sophisticated. Artists such as the Cars, Devo, the Talking Heads, and the Human League leapt into the Top 40 with a novel sound that broke with the staid rock clichés of the 1970s and pointed the way to a more modern pop style.

In Are We Not New Wave? Theo Cateforis provides the first musical and cultural history of the new wave movement, charting its rise out of mid-1970s punk to its ubiquitous early 1980s MTV presence and downfall in the mid-1980s. The book also explores the meanings behind the music's distinctive traits—its characteristic whiteness and nervousness; its playful irony, electronic melodies, and crossover experimentations.

Theo Cateforis is Assistant Professor of Music History and Cultures in the Fine Arts Department at Syracuse University. His research is in the areas of American Music, Popular Music Studies, and Twentieth-Century Art Music. He was editor of the anthology The Rock History Reader.

The University of Michigan Press: What were the forces that led to the rise of new wave?

Theo Cateforis: New wave initially circulated as a synonym for the punk rock movement that emerged in the mid-1970s. Punk rock or new wave bands overwhelmingly expressed their dissatisfaction with the prevailing rock trends of the day. They viewed bombastic progressive rock groups like Emerson Lake and Palmer and Pink Floyd with disdain, and instead channeled their energies into a more stripped back sound—one that echoed the earlier rock and roll spirit of the late 1950s and early 60s. The media, however, portrayed punk groups like the Sex Pistols and their fans as violent and unruly, and eventually punk acquired a stigma—especially in the United States—that made the music virtually unmarketable. At the same time, a number of bands, such as the Cars, the Police and Elvis Costello and the Attractions, soon emerged who combined the energy and rebellious attitude of punk with a more accessible and sophisticated radio-friendly sound. These groups were lumped together and marketed exclusively under the label of new wave. Before long new wave was seen as a more-commercialized version of punk, and in many people’s mind this separation has remained intact ever since. So, in this respect the story of the rise of new wave is one that is intimately tied to the music industry and its desire to harness the power of punk in a more palatable form.

UMP: What defines new wave?

TC: As I argue in my book, new wave is best understood as a style of “modern” pop music. The idea of being modern, of course, is complex. On the one hand, it simply meant that the new wave groups that emerged in the late 70s separated themselves from the mainstream in some way that was seen as fresh and a bit daring. For some bands, wearing sleek skinny ties or retro 60s mod fashions was enough to suggest a modern sensibility; for other new wave artists, the use of minimalist arrangements and synthesizers or the cross-cultural borrowings of groups like the Talking Heads symbolized a new modern sound. For many people, the music videos that came to be associated with new wave—whether it was the bizarre, and often satirical, avant-garde creations of Devo or the heavily stylized, somewhat cinematic settings, of British groups like the Adam and the Ants and Duran Duran—represented new wave at its most modern.

UMP: What made new wave a significant musical movement?

TC: Much new wave music was notable for its upbeat, dance-inspired tempos…an element that had largely gone missing from rock music in the 1970s when groups instead shaped their sound to fit the spectacular stadium and arena settings that defined the era. It is no accident that new wave thrived during the late 70s and early 80s in small clubs and the numerous rock discos that had begun to appear as the original disco movement itself was beginning to fade. New wave rock bands often drew on dance-related styles—whether it was disco and funk or reggae and ska in a way that few mainstream rock acts did. In doing so, new wave refused the older late 60s hippie and hard rock legacy that prevailed among groups like Foreigner and Journey. New wave bands also embraced both the rock music and the pop culture of the past in a way that other mainstream rock bands did not. A typical new wave song could include anything from rockabilly to Motown reference points. Or in the case of a group like the Knack, one heard a power pop sound that drew on the early music of the Beatles and the Who. Sometimes this allusion to the past was ironic, other times it was completely sincere. In either case it served to define the new wave as something fresh and new compared to the mainstream rock trends of the day.

UMP: What is new wave's legacy?

TC: New wave has enjoyed a strong legacy within not only rock, but hip hop as well. A number of rock groups in the early 2000s, ranging from the Strokes to Hot Hot Heat and the Killers were touted as “new” new wave bands, largely thanks to their stripped back sound, upbeat tempos and a sense of irreverent, slightly rebellious attitude. New wave has also proven to be a popular sound for various Disney artists ranging from Hannah Montana to the Jonas Brothers. Probably the most lasting of new wave’s legacies is its association with the synthesizer. At the time that artists like Gary Numan, Soft Cell, the Human League and Thomas Dolby invaded the pop charts in the early 80s with their synthesized arrangements, they introduced a sound that was both novel and futuristic. In the decades since, popular music has become more and more synthesized, especially within hip hop and R&B. It is more common these days to hear hip hop artists sampling 80s synth pop music because it fits so seamlessly within today’s contemporary music styles.

UMP: How is new wave regarded today?

TC: New wave has assumed a place of prestige within the history of rock, largely thanks to groups like the Talking Heads who embodied the more self-consciously experimental and socially aware side of the movement. New wave was very much a favorite of rock critics in the late 1970s, and it has remained a style that is often viewed as more sophisticated, intelligent and cutting edge than many other rock styles. Along with the Talking Heads, new wave artists like the Pretenders, Blondie, Police and Elvis Costello are all in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, a sign of the lasting impact and influence that they had on rock music as a whole. The synth pop bands that came to be associated with new wave in the early 80s—groups like the Human League, Depeche Mode, Spandau Ballet and Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark—all enjoyed greater success and notoriety in their homeland of England than in the United States. American rock critics were less quick to warm to them, perhaps because they embodied a more pop than rock attitude. Over time, however, these groups have come to be regarded as cornerstones of a strong synth pop tradition, one that has proven to be extremely influential on music of the past decade, ranging from the Postal Service to Rihanna and La Roux.

To read more about Are We Not New Wave? Modern Pop at the Turn of the 1980s by Theo Cateforis, visit The University of Michigan Press at /isbn/9780472034703.

To listen to The University of Michigan Press podcasts, visit our podcast page at: www.press.umich.edu/podcasts/index.jsp.